BY: SAI MANOGNA (MSIWM012)

Introduction :

Any disease caused by bacteria involves bacterial diseases. Bacteria, which are small types of life that can only be seen through a microscope, are microorganisms. Viruses, some fungi, and some parasites include other types of microorganisms. Millions of bacteria usually reside in the skin, intestines, and genitals. The vast majority of bacteria cause no disease, and many bacteria are beneficial and even required for good health. Often, these bacteria are referred to as good bacteria or healthy bacteria.

Pathogenic bacteria are considered dangerous bacteria that cause bacterial infections and illnesses. When these invade the body and begin to replicate and crowd out healthy bacteria or develop in typically sterile tissues, bacterial diseases occur. Toxins that damage harmful bacteria can also release the body.

Typhoid :

An infectious, potentially life-threatening bacterial infection is typhoid fever, also called enteric fever. Typhoid fever is caused by the Salmonella enteric serotype Typhi bacterium (also known as Salmonella Typhi), carried into the blood and digestive tract by infected humans and spreads by food drinking water contaminated with infected feces to others. Typhoid fever signs include fever, rash, and pain in the abdomen.

Fortunately, typhoid fever, particularly in its early stages, is treatable, and if one chooses to live in or fly to high-risk areas of the world, a vaccine is available to help prevent the disease.

Incubation Period :

Typhoid and paratyphoid infections have an incubation period of 6-30 days. With steadily rising exhaustion and a fever that rises daily from low-grade to as high as 102 ° F to 104 ° F ( 38 ° C to 40 ° C) by the third to the fourth day of illness, the onset of illness is insidious. In the morning, fever is usually the lowest, peaking in the late afternoon or evening.

Pathophysiology :

1. When present in the gut, all pathogenic Salmonella species are swallowed up by phagocytic cells, moving them through the mucosa and presenting them to the lamina propria macrophages.

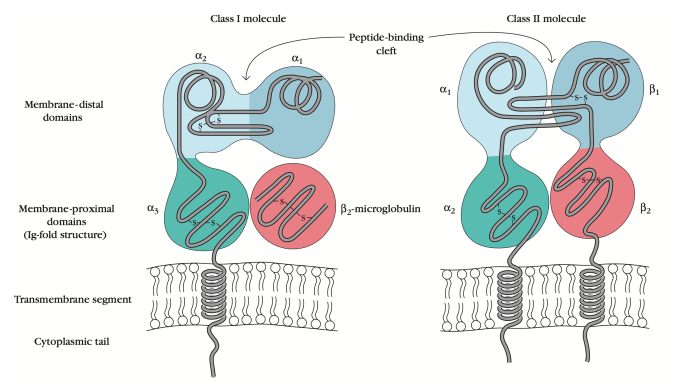

2. Across the distal ileum and colon, nontyphoidal salmonellae are phagocytized. Macrophages identify pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as flagella and lipopolysaccharides with the toll-like receptor (TLR)-5 and TLR-4 / MD2 / CD-14 complex.

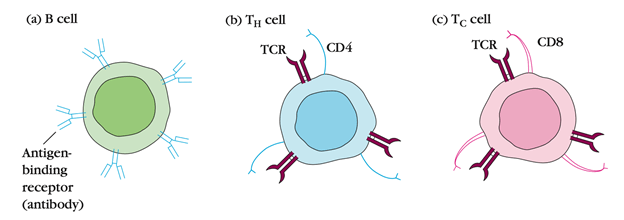

3. Macrophages and intestinal epithelial cells are then attracts the interleukin 8 (IL-8) T cells and neutrophils, inducing inflammation and suppressing the infection.

4. Unlike the nontyphoidal salmonellae, S typhi and paratyphi penetrate mainly via the distal ileum into the host system. They have specialized fimbriae that bind to the epithelium over lymphoid tissue clusters in the ileum, the critical point of relay for macrophages moving into the lymphatic system from the stomach.

5. The bacteria then attract more macrophages by activating their host macrophages.

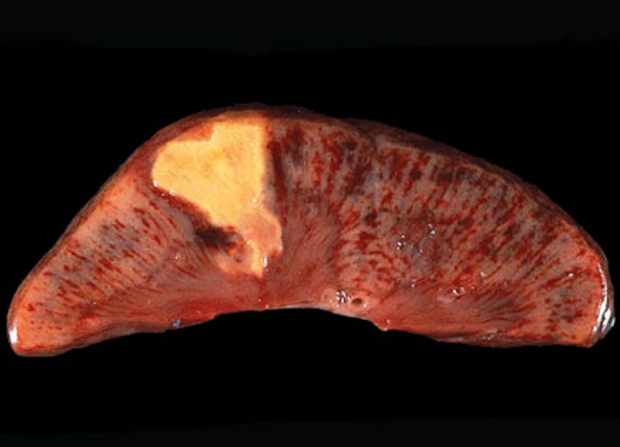

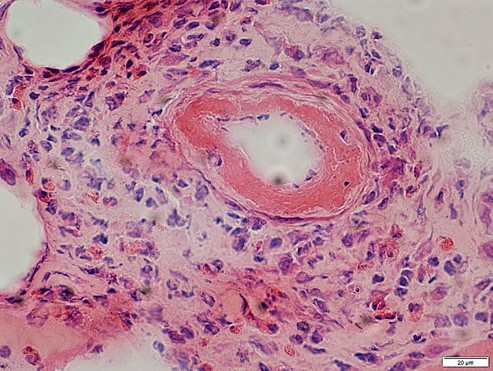

6. Typhoidal salmonella co-opts the cellular machinery of the macrophages for their reproduction, as they are transported to the thoracic duct and lymphatics to the mesenteric lymph nodes and then to the reticuloendothelial tissues of the spleen, bone marrow, liver, and lymph nodes.

7. Once there, until some critical density is reached, they pause and begin to multiply. Afterward, to reach the rest of the body, the bacteria cause macrophage apoptosis, breaking out into the bloodstream.

8. By either bacteria or direct extension of infected bile, the bacteria then invade the gallbladder. The effect is that in the bile, the organism re-enters the gastrointestinal tract and reinfects patches of Peyer.

9. Usually, bacteria that do not reinfect the host are shed in the stool and are then available for other hosts to invade.

Epidemiology :

The International

Worldwide, typhoid fever occurs mostly in developing countries where sanitary conditions are low. In Asia, Latin America, Africa, the Caribbean, and Oceania, typhoid fever is endemic, but 80 percent of cases originate from Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Laos, Nepal, Pakistan, or Vietnam. In underdeveloped countries, typhoid fever is the most common. About 21.6 million people are infected by typhoid fever (incidence of 3.6 per 1,000 population), and an estimated 200,000 people are killed every year.

Most cases of typhoid fever occur among foreign travelers in the United States. The average annual incidence of typhoid fever by county or area of departure per million travelers from 1999-2006 was as follows:

Outside Canada / United States, Western Hemisphere-1.3

Africa-7.6 Africa

Asia-10.5.

India-89 (in 2006 122)

Complete (except for Canada / United States, for all countries)-2.2

Morbidity / Mortality :

Typically, typhoid fever is a short-term febrile condition with timely and effective antibiotic care, requiring a median of 6 days of hospitalization. It has long-term sequelae and a 0.2 percent mortality risk when treated. Untreated typhoid fever is a life-threatening disease that lasts many weeks, frequently affecting the central nervous system, with long-term morbidity. In the pre-antibiotic age, the case fatality rate in the United States was 9 -13%.

Sex :

Fifty-four percent of cases of typhoid fever recorded between 1999 and 2006 in the United States included males. Moreover, race has no predilection.

Age :

Many confirmed cases of typhoid fever include children of school age and young adults. The true incidence is, however, thought to be higher among very young children and babies. The presentations may be atypical, that ranges from a mild febrile disease to severe convulsions, and the infection of S.typhi may go unrecognized. In the literature, this could account for contradictory reports that this category has very high or very low morbidity and mortality rate.

Symptoms :

Typhoid fever symptoms typically occur five to 21 days after food or water infected with Salmonella Typhi bacteria is consumed and can last up to a month or longer. Typical Typhoid Fever signs include:

i. Pressure in the abdomen and tenderness

ii. Perplexity

iii. Fatigue and Weakness

iv. Trouble focusing

v. Constipation or diarrhea

vi. Headaches

vii. The Nosebleeds

viii. A dry cough

ix. Impoverished appetite

x. Rash (small, flat, red rashes that are also known as rose spots on the belly and chest)

xi. Lethargy

xii. Swollen lymph ganglions

xiii. Chills and Fever. With typhoid fever, persistent fever of 104 degrees Fahrenheit is not rare.

Symptoms: life-threatening

Typhoid fever, including intestinal bleeding, kidney failure, and peritonitis, may lead to life-threatening complications. If they are with anyone who has any of these signs, seek urgent medical attention :

Bloody stools or severe rectal bleeding

A shift in consciousness or alertness level

Confusion, delirium, disorientation, or hallucinations

Unexplained or chronic dizziness

Dry, broken lips, tongue, or mouth

Unresponsiveness or lethargy

Not urinating tiny quantities of tea-colored urine or urinating it.

Extreme pain in the abdomen

Extreme diarrhea in patients

Extreme signs in infants include sunken fontanel (soft spot) at the top of the head, lethargy, no weeping tears, little or no wet diapers, and diarrhea. Infants two months of age or younger, be especially concerned about fever.

Causes :

The Salmonella Enteric Serotype Typhi (Salmonella Typhi) bacterium is responsible for typhoid fever. Via ingestion of infected food and water, Salmonella Typhi can enter and infect the body. By being washed in polluted water or being touched by an infected person with unwashed hands, food can become contaminated with the bacteria. Drinking water can become infected with untreated Salmonella Typhi-containing sewage.

Risk factors :

A variety of variables improves the chances of contracting typhoid fever. In developing, non-industrialized countries, typhoid fever is a significant health threat, although rare in the United States, Canada, and other industrialized countries. Factors of vulnerability include:

i. Near contact with individuals infected or recently infected

ii. Travel to areas with more frequent and widespread outbreaks of typhoid fever, such as India, Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America

iii. Avoiding contact with a person who has or has signs of typhoid fever, such as abdominal pain, headache, and fever

iv. Residence in a developing world or continent with inadequate treatment facilities for water and sewage or poor hygiene practices

v. Due to diseases such as HIV / AIDS or drugs such as corticosteroids, the compromised immune system

vi. Do not eat fruits and vegetables that are unable to peel. Eating fully cooked, hot, and still steaming foods. Unless it is made from distilled water, drinking only bottled water and not using ice

vii. Before visiting high-risk areas, having vaccinated against typhoid fever

viii. During and after contact with an individual who has typhoid fever or with an individual who has signs of typhoid fever, such as abdominal pain, headache, rash, and fever, washing hands regularly with soap and water for 15 seconds

ix. Washing hands regularly for at least 15 seconds with soap and water, particularly before handling food and after using the toilet, touching feces, and changing diapers

Diagnosis :

1. Salmonella bacteria infiltrate the small intestine following the ingestion of infected food or drink and temporarily enter the bloodstream.

2. The bacteria are transported into the liver, spleen, and bone marrow by white blood cells, replicating and re-enter the bloodstream.

3. At this point, people develop symptoms, including fever. Bacteria invade the biliary system, gallbladder, and the intestinal lymphatic tissue.

4. Here, in high numbers, they multiply. In the digestive tract, the bacteria move and can be found in stool samples.

5. Blood or urine samples will be used to diagnose if a test result is not exact.

Treatment :

Typhoid fever is a treatable condition, and a complete course of antibiotics, such as ampicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or ciprofloxacin, may also be used to cure it. Treatment can include rehydration with intravenous fluids and electrolyte replacement therapy in some severe cases. Usually, with care, symptoms improve within two to four weeks. If they have not been treated completely, symptoms may return. One needs to take the antibiotics for as long as needed to treat typhoid fever and follow up with the doctor for a series of blood and stool tests to ensure that they are no longer infectious.

Few people infected with Salmonella Typhi become carriers, which indicates that the bacteria are present in the intestines and bloodstream and are shed in the stool even after they no longer have disease symptoms. Because of the carrier effect, it is essential to understand that they might still transmit the disease by contaminating food and water even after receiving treatment for typhoid fever. Before traveling outside developed regions, such as the United States, Canada, northern Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, it is vital to avoid the disease by getting vaccinated. During epidemic outbreaks, immunizations are also recommended, although the vaccination is not successful.

Prevention :

A larger number of typhoid cases usually occur in countries with less access to clean water and washing facilities.

Immunization :

Vaccination is advised while traveling to a region where typhoids are prevalent.

It is recommended to get vaccinated against typhoid fever before traveling to a high-risk area.

Oral treatment or a one-off injection can be done :

Oral: an attenuated, live vaccine. It consists of 4 tablets, one of which is taken every other day, the last of which is taken one week before departure.

Shoot, the inactivated vaccine, was given two weeks before the ride.

Vaccines are not 100 percent successful, and when eating and drinking, caution should always be exercised.

Two forms of typhoid vaccine are available, but a more potent vaccine is still required. The vaccine’s live, oral form is the strongest of the two. It also protects individuals from infection 73 percent of the time after three years. This vaccine has more side effects, however. If the person is currently ill or if he or she is under the age of 6 years, vaccination should not begin. The live oral dose should not be taken by someone who has HIV. There may be adverse effects of a vaccine. One in every 100 people is going to feel a fever. There may be stomach complications following the oral vaccine, nausea, and headache. For any vaccine, however, serious side effects are uncommon.

Typhoid removal :

Even if typhoid symptoms have passed, it is still possible to bear the bacteria, making it impossible to stamp out the disease because when washing food or communicating with others, carriers whose symptoms have terminated may be less vigilant.

Prevention of Infection :

Via touch and ingestion of contaminated human waste, typhoid is propagated. This can happen through a source of water that is tainted or when food is treated.

Some general rules to obey while traveling to help reduce the risk of typhoid infection are the following:

i. Drink water, preferably carbonated, in glasses.

ii. Do not have ice for drinks. Stop raw fruit and vegetables, cut the fruit, and not eat the cut on your own. Eat only food that is still hot, and avoid eating at street food stands.

iii. If it is impossible to acquire bottled water, ensure the water is heated for at least one minute on a rolling boil before consumption.

iv. Be wary of eating something that anyone else has dealt with.

Related Disorders :

There may be similar symptoms of the following conditions to those of typhoid fever. For a differential diagnosis, similarities may be helpful:

Salmonella Poisoning :

In foodborne diseases, this is the most common cause of disease. These bacteria can contaminate meat, dairy, and vegetable products. In warm weather and children under the age of seven, outbreaks are more prevalent. The most common initial symptoms are nausea, vomiting, and chills. These are accompanied by stomach pain, diarrhea, and fever that can last for several weeks to five days. Intoxication with salmonella is a type of gastroenteritis. The CDC reports about 2 to 4 million salmonellosis cases per year in the United States.

Cholera :

Cholera is a bacterial infection characterized by extreme diarrhea and vomiting that affects the whole small intestine. A toxin produced by the bacteria Vibrio cholerae is the source of the symptoms. The disease is transmitted by drinking water or consuming fish, vegetables, and other foods contaminated with Cholera’s excrement.

Botulism :

Botulism is also a form of gastroenteritis caused by a bacterial toxin. A neuromuscular poison is this toxin. In three types, it occurs foodborne, wound, and infantile botulism. The foodborne type is the most popular. Besides nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach pain, the patient can feel exhaustion, fatigue, headache, and dizziness.

Ptomaine Poisoning in the United States’ fourth most prevalent cause of bacterial foodborne disease. It is caused by the enterotoxin protein released after consuming foods that are contaminated, usually meat products. Extreme stomach cramps and diarrhea are characteristics of the disease. Nausea also happens sometimes. Vomiting and fever are rare.