BY: SAI MANOGNA (MSIWM014)

Introduction:

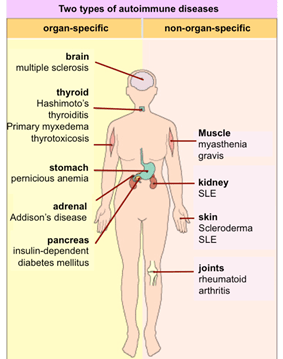

Hepatitis is the general term for liver inflammation, caused by several causes, both infectious such as bacterial, viral, parasitic and fungal, and non-infectious such as alcohol, autoimmune, drugs, and metabolic diseases. A disorder that happens when our body makes antibodies to liver tissue is autoimmune hepatitis.

The liver is situated in the right upper region of the abdomen. It performs many critical functions in our body that influence metabolism, including:

- Production of bile.

- Filtering the body’s contaminants.

- Degradation of Carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.

- Activation of enzymes, specific proteins that are important to the functions of the body.

- Excretion of bilirubin (a red blood cell breakdown product), cholesterol, hormones, and drugs.

- Blood protein synthesis, including albumin and clotting factors.

- Glycogen, vitamins (A, D, E, and K) and minerals are processed.

Types of viral hepatitis:

Hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E contain viral infections of the liver known as hepatitis. A specific virus is responsible for each kind of virally transmitted hepatitis. Hepatitis A is often a short-term, acute infection, while hepatitis B, C, and D are most likely to become chronic and permanent. Hepatitis E is typically acute, but in pregnant women, it can be particularly hazardous.

Hepatitis A Virus (HAV):

Hepatitis A is due to a hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection. This form of hepatitis is most frequently transmitted from a person infected with hepatitis A by consuming food or water contaminated by feces.

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

HBV is transmitted through contact with infectious body fluids that contain the hepatitis B virus (HBV), such as blood, vaginal secretions, or semen.

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV):

Hepatitis C comes from the virus (HCV) of hepatitis C. Hepatitis C is transmitted through direct contact with infectious body fluids, usually through sexual contact and injection drug use.

Hepatitis D Virus (HDV):

Hepatitis D also called delta hepatitis, is a severe hepatitis D virus (HDV)-induced liver disease. By direct contact with contaminated blood, HDV is contracted. Hepatitis D is a rare type of hepatitis that occurs only in combination with infection with hepatitis B. Without the involvement of hepatitis B; the hepatitis D virus cannot replicate.

Hepatitis E Virus (HEV):

Hepatitis E is an illness caused by the hepatitis E virus (HEV) that is waterborne. Hepatitis E is found predominantly in poorly sanitized environments and usually results from the ingestion of fecal matter that contaminates water source.

Hepatitis G Virus (HGV):

Recently, the hepatitis G virus (HGV, also called GBV-C) has been discovered and resembles HCV, but flaviviruses are more closely related. The virus and its effects are being studied, and it is uncertain about its role in causing disease in humans.

Incubation period:

The period between hepatitis infection and the onset of the illness is called the period of incubation. Depending on the individual hepatitis virus, the incubation time varies. The incubation period for HAV is approximately 15 to 45 days;

hepatitis B virus is 45 to 160 days;

hepatitis C virus, approximately two weeks to 6 months.

Pathophysiology:

Hepatitis A :

1. Several weeks of malaise, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and elevated levels of aminotransferase mark the usual acute HAV infection cases.

2. In more severe cases, jaundice occurs. In comparison to the classic image of elevated aminotransferase levels, some patients experience cholestatic hepatitis, characterized by the production of an elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level.

3. During a year, patients can experience multiple relapses. Infection with HAV does not spread and does not contribute to chronic hepatitis.

Hepatitis B:

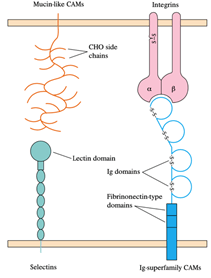

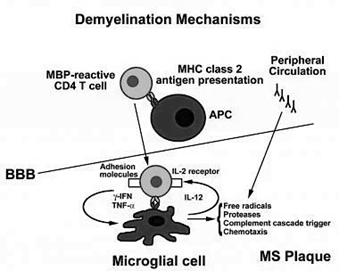

The hepatitis B virus ( HBV) may be hepatocyte-directly cytopathic. Cytotoxicity mediated by the immune system plays a predominant role in causing liver damage, however. The immune attack is guided on the cell membranes of infected hepatocytes by human leukocyte antigen ( HLA) class I-restricted CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocytes that recognize the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg).

Acute Infection :

1. Some patients have elevated serum levels of HBV DNA and a positive blood test for the presence of HBeAg but have normal levels of alanine aminotransferase ( ALT) and display minimal histologic evidence of liver damage, particularly those infected as newborns or as young children. These people are in the disease’s so-called “immune-tolerant phase.

2. years later, when the liver experiences aggressive inflammation and fibrosis, some but not all of these individuals can enter the “immune-active phase” of the disease in which the HBV DNA can remain elevated.

3. In this time, an elevated ALT level is also noted. The immune-active process usually ends with HBeAg loss and the production of HBeAg (anti-HBe) antibodies.

4. The “inactive carrier state”, which is formerly referred to as the “safe carrier state, can be reached by individuals who convert from an HBeAg-positive to an HBeAg-negative.

5. These people are asymptomatic, have regular test results for liver chemistry, and have regular or minimally abnormal biopsy results for the liver.

Inactive carriers remain, via parenteral or sexual transmission, contagious to others. Ultimately, inactive carriers can produce anti-HBs and clear out the virus.

Chronic Infection:

Either HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative can be considered for patients with chronic hepatitis. About 80% of chronic HBV cases are HBeAg-positive, and 20% are HBeAg-negative in North America and Northern Europe. 30-50 percent of cases are HBeAg-positive and 50-80 percent HBeAg-negative in Mediterranean countries and some areas of Asia.

1. Signs of active viral replication are present in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis with HBV DNA levels greater than 2 ×104 IU / mL. Levels of HBV DNA can be as high as 1011 IU / mL.

2. HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis patients were probably infected at some stage with wild-type viruses. They also developed a mutation in either the precore or the viral genome’s main promoter region over time.

3. HBV continues to replicate in such patients with a pre-core mutant state, but HBeAg is not formed. Patients with a core mutant state tend to have HBeAg production downregulated.

4. The vast majority of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients have a serum level of HBV DNA more significant than 2000 IU / mL.

5. HBeAg-negative patients usually have lower levels of HBV DNA than HBeAg-positive patients do. The HBV DNA level is usually no higher than 2 ×104 IU / mL.

Hepatitis C:

1. Patients with HCV-induced cirrhosis also have an increased risk of developing Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), particularly in the aspect of co-infection with HBV.

2. HCC occurs in 1-5 percent of HCV-induced cirrhosis patients. In patients with HCV-induced cirrhosis, routine screening (e.g., ultrasonography and AFP testing every 6 months) is recommended to rule out HCC growth.

Hepatitis D:

1. Acute hepatitis resulting from this can be mild or severe. Similarly, after acute exposure to both viruses, the risk of developing chronic HBV and HDV infection is the same as the incidence of developing chronic HBV infection after acute HBV exposure (approximately 5 percent in adults).

2. Chronic HBV and HDV disease continues to lead to cirrhosis more quickly than chronic HBV infection alone.

3. The introduction of HDV into a person already infected with HBV may have drastic implications.

4. Superinfection may give the appearance of a sudden worsening or flare of hepatitis B to HBsAg-positive patients. Superinfection with HDV may result in FHF.

Hepatitis E:

Traditionally, it has not been assumed that HEV causes chronic liver disease. In organ transplant recipients, however, several studies have identified chronic hepatitis due to HEV. Dense lymphocytic portal infiltrates with interface hepatitis were revealed by liver histology, close to hepatitis C infection results. Some cases have moved into cirrhosis.

Etiology:

Hepatitis A Virus:

The most commonly transmitted HAV through the fecal-oral pathway. Cases of HAV-associated transfusion or inoculation-induced disease are rare.

HAV infection is prevalent, in the less-developed nations of Asia, Africa, and Central and South America, the Middle East has an exceptionally high prevalence. Most patients are infected when they are young kids in these areas. There is a chance of infection for uninfected adult travelers who enter these areas.

Hepatitis B Virus:

The presence of a surface antigen for hepatitis B (HBsAg) is characterized by HBV infection. Chronic HBV infection occurs in about 90-95 percent of neonates with acute HBV infection and 5 percent of adults with acute infection. The infection is removed in the remaining patients, and these patients develop lifelong immunity to recurring infections.

Perinatal transmission:

Perinatal transmission occurs in the vast majority of HBV cases around the world. During the intrapartum phase or, occasionally, in utero, infection tends to occur. Typically, neonates affected by perinatal infection are asymptomatic. The role of breastfeeding in the transmission is unclear, although breast milk may contain HBV virions.

Sexual transmission:

HBV is more readily transmitted than HCV or the human immunodeficiency virus ( HIV). Vaginal intercourse, genital-rectal intercourse, and oral-genital intercourse are associated with infection. Approximate 30 percent of HBV infected patients’ sexual partners also develop HBV infection. HBV cannot, however, be transmitted by kissing, touching, or household touch (e.g., towel sharing, eating utensils, or food). It is estimated that sexual activity accounts for as many as 50 percent of US cases of HBV.

Sporadic Cases:

The cause of HBV infection is unclear in roughly 27 percent of cases. Indeed, some of these incidents may be due to sexual reproduction or blood contact.

Hepatitis C Virus:

HCV is the most prevalent cause of non-A, non-B (NANB) parenteral hepatitis worldwide. In 0.5-2 percent of populations in nations around the world, hepatitis C is prevalent. In haemophilia patients and IDUs, the highest rates of disease prevalence are found.

Transmission via a transfusion of blood :

The occurrence of transfusion-associated HCV infection has been significantly decreased by screening the US blood supply. Before 1990, the transfusion of infected blood products accounted for 37-58 percent of acute HCV infection (then known as NANB); currently, only about 4 percent of acute cases are due to transfusions. The chance of getting a hepatitis C-infected blood donation is 1 in 2 million. In dialysis units, acute hepatitis C remains a vital concern where the risk of HCV infection in patients is approximately 0.15 percent per year.

Transmission by the use of intravenous and intranasal medications:

IDU remains a useful HCV transmission mode. Around 60 percent of new HCV infection cases account for the use of intravenous ( IV) drugs and the sharing of paraphernalia used in the intranasal snorting of cocaine and heroin. HCV has been exposed to more than 90 percent of patients with a history of IDU.

Sexual transmission: Roughly 20 percent of hepatitis C cases tend to be due to sexual contact. In comparison to hepatitis B, hepatitis C is contracted by about 5 percent of the intimate partners of those infected with HCV.

HCV-infected individuals should be aware of the potential for sexual transmission. The presence of antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV) should be tested on sexual partners. For patients with multiple sex partners, safe-sex precautions are recommended. For patients with a steady sexual partner, existing recommendations do not encourage the use of barrier precautions. Patients can, however, avoid sharing razors with others and toothbrushes. Moreover, contact with the blood of patients should be avoided.

Perinatal transmission:

In 5.8 percent of infants born to mothers infected with HCV, perinatal transmission of HCV occurs. In children born to mothers co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and HCV, the risk of perinatal transmission of HCV is higher (about 18 percent).

Hepatitis D Virus:

HBV’s presence allows HDV to replicate, so HDV infection occurs only in patients who are HBsAg-positive. Patients may acquire HDV as a co-infection (at the same time that they contract HBV), or HDV may superinfect patients who are chronic carriers of HBV. In the United States, hepatitis D is not a reportable disease, so reliable data about HDV infections are scarce. It is estimated, however, that approximately 4-8 percent of acute hepatitis B cases include HDV co-infection.

In IDU, the sharing of infected needles is considered the most common means of HDV transmission. HDV prevalence rates ranging from 17- 90% have been identified for IDUs that are also positive for HBsAg. It also explains sexual transmission and perinatal transmission. In Greece and Taiwan, the prevalence of HDV in sex workers is high.

Hepatitis E Virus:

The primary cause of enterally transmitted hepatitis from NANB is HEV., which is transmitted through the fecal-oral route, and in some parts of less developed countries, where most outbreaks occur, it tends to be endemic. HEV may also be vertically transmitted to HEV-infected mothers’ infants. High neonatal mortality is correlated with it.

Anti-HEV antibodies in 29 percent of urban children and 24 percent of rural children in northern India were present in one study. Sporadic infections are found in individuals who migrate to these regions from Western countries.

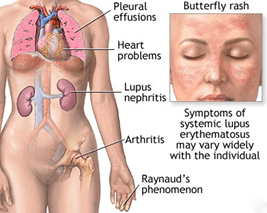

Symptoms:

There are little to no disease signs in many patients infected with HAV, HBV, and HCV. They do not have symptoms at first if they have contagious types of hepatitis that are chronic, such as hepatitis B and C. Symptoms cannot happen until the injury impairs liver function.

Flu-like symptoms are the most common, including:

Appetite deficit, Fever, Fatigue, Aching from the belly, Vomiting, Nausea, Feebleness

Symptoms that are less common include:

Dark-colored urine, fever, jaundice, and stools that are light-colored.

Causes:

Alcohol as well as other toxins:

Liver damage and inflammation can be caused by excessive alcohol consumption. It is referred to as alcoholic hepatitis occasionally. Liver cells are directly injured by alcohol, causing irreversible damage over time, leading to liver failure and cirrhosis, liver thickening, and scarring. Other toxic causes of hepatitis are drug overuse or poisoning and exposure to poisons.

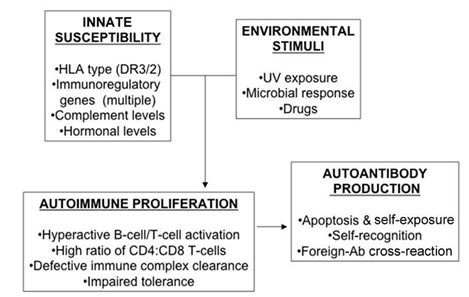

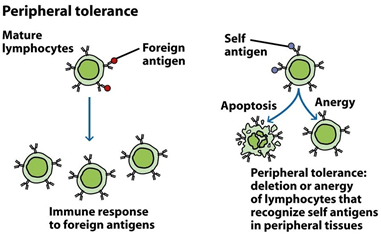

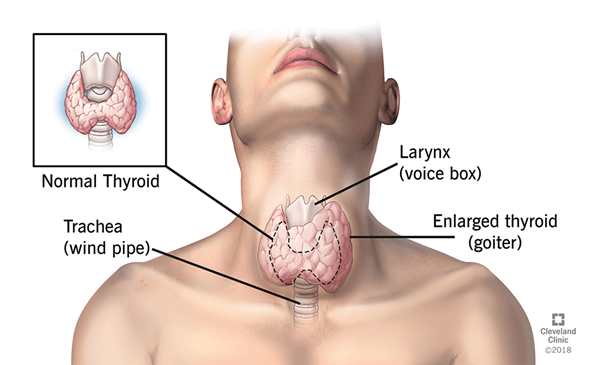

Autoimmune system responses:

The immune system identifies the liver as a foreign entity in some situations and starts to attack it. It induces persistent inflammation that can vary from mild to severe, often impeding the liver’s function. In women, it is 3 times more common than in men.

Risk Factors:

People at the highest risk for the production of viral hepatitis. They are:

- Staff in the health care professions

- Patients with HIV

- Individuals with several sexual partners

- Intravenous drug users

- Asians and islanders of the Pacific

- Workers in sewage and water treatment

- People who receive blood clotting factors with hemophilia

Once a common means of transmitting viral hepatitis, transfusion of blood is now a rare cause of hepatitis. Among lower socio-economic and poorly educated people, viral hepatitis is commonly thought to be 10 times more common. Approximately one-third of all hepatitis cases are from an undisclosed or unidentified source. To be infected with a hepatitis virus, a person does not have to be in a high-risk category. Food and water pollution with HAV raises risks in countries with low sanitation. Some daycare centers may become infected with HAV, so kids are at a higher risk of HAV infections at those centers.

Diagnosis:

History And Physical Examination

The physician will first take history to assess any risk factors for contagious or non-infectious hepatitis to diagnose hepatitis.

They gently press down on the abdomen during a physical examination to see if there is pain or tenderness and feel if the liver has been swollen. During the test, if skin or yellowish eyes were also examined.

Tests for Liver Function:

Tests for liver function use blood samples to assess how the liver functions effectively. The first indication might be inconsistent results from these tests, mainly if they do not display any physical exam signs for liver disease. High levels of liver enzymes can mean that liver is stressed, damaged, or not correctly functioning.

Other Tests for Blood:

Physicians would typically prescribe more blood tests to detect the cause of the problem if liver function tests are irregular. These tests can check for hepatitis-causing viruses. In conditions such as autoimmune hepatitis, they may also be used to search for normal antibodies.

Ultrasound:

An abdominal ultrasound uses ultrasonic waves to closely inspect the liver and associated organs to create a picture of the abdomen’s organs. It will expose:

Abdomen fluid:

Harm to the liver or enlargement

Tumors in the liver

Gallbladder disorders

The pancreas even shows up on ultrasound images occasionally. In identifying the cause of abnormal liver function, this can be a practical examination.

Biopsy of the Liver:

An invasive procedure of taking a sample of tissue from the liver is a liver biopsy. It can be carried out with a needle through the skin and does not require surgery. Usually, before the biopsy sample is taken, an ultrasound is mandatory.

This test helps to assess if the liver has been damaged by infection or inflammation. Some areas that appear abnormal in the liver may also be sampled using it.

Treatment:

Both Acute and chronic viral hepatitis are viewed differently. Acute viral hepatitis treatment requires sleeping, relieving symptoms, and ensuring sufficient fluid intake. Treatment of chronic viral hepatitis requires drugs to kill the virus and prevent further damage to the liver.

Acute Hepatitis:

Initial treatment consists of relieving nausea, vomiting, and stomach pain in patients with acute viral hepatitis. Medications or substances that may have harmful effects on patients with abnormal liver function (for example, acetaminophen, alcohol) should be considered carefully. Only certain medicines that are deemed appropriate should be administered because the liver is not naturally able to remove drugs, and drugs may accumulate and reach toxic blood levels. Also, sedatives and “tranquilizers” are avoided because they can accentuate liver failure’s brain effects and induce coma and lethargy. As alcohol is harmful to the liver, the patient must abstain from consuming alcohol. To avoid dehydration caused by vomiting, it is sometimes essential to have intravenous fluids. For therapy and intravenous fluids, patients with extreme nausea and vomiting may need to be hospitalized.

Acute HBV is not treated with medications that are antiviral agents. Though rarely diagnosed, acute HCV can be treated with some of the medicines used to treat chronic HCV. In 80 percent of patients who do not eliminate the virus early, HCV treatment is mainly recommended. The procedure results in virus clearance in most patients.

Chronic Hepatitis:

Treatment of chronic HBV and HCV infections typically requires medicine or combinations of virus eradication drugs. In chronic hepatitis, alcohol aggravates liver damage and can cause more rapid progression to cirrhosis. Consequently, chronic hepatitis patients should avoid drinking alcohol. Cigarette smoking can also worsen liver disease and should be prevented.

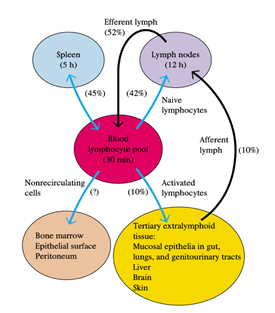

Prevention :

Hepatitis prevention requires steps to prevent exposure to viruses, the use of immunoglobulin in case of exposure, and vaccines. Immunoglobulin administration is called passive defense since the patient receives antibodies from patients that have had viral hepatitis. As killed viruses or non-infectious components of viruses are given to stimulate the body to generate its antibodies, vaccination is called active defense.

Avoidance of virus exposure:

Like any other disease, avoiding viral hepatitis is superior to depending on the treatment. Taking measures to avoid exposure to blood (exposure to dirty needles), semen (unprotected sex), and other bodily secretions and waste (stool, vomit) from another human can help prevent any of these viruses from spreading.

By Immunoglobulins:

Immune serum globulin (ISG) is a human serum which contains hepatitis A antibodies. In individuals that have been exposed to hepatitis A, ISG may be given to avoid infection. ISG operates immediately upon administration, and the security period is several months long. ISG is typically given to travelers to regions of the world where there is a high infection rate with hepatitis A and near or domestic interaction with hepatitis A patients. With few side effects, ISG is stable.

The immune globulin of hepatitis B, or HBIG (BayHep B), is a human serum containing hepatitis B antibodies. HBIG is made of plasma (a blood product) believed to contain a high concentration of hepatitis B surface antigen antibodies. HBIG is almost always effective at avoiding infection if administered within ten days of exposure to the virus. However, even if administered a bit later, HBIG can reduce the severity of HBV infection. The defense against hepatitis B lasts for approximately three weeks after the administration of HBIG. HBIG is also given at birth to infants born to mothers confirmed to be infected with hepatitis B. HBIG is often given to individuals exposed to HBV by an infected person due to sexual contact or to healthcare workers inadvertently stuck by a needle known to be contaminated with blood.

Vaccinations:

Hepatitis A:

In the US, the hepatitis A vaccine (Havrix, Vaqta) is available with two hepatitis A vaccines. They both contain the inactive (killed) virus of hepatitis A. For adults, it is preferable to take two doses of vaccination. After the first dose, protective antibodies develop within two weeks in 70% of vaccine recipients and within four weeks in nearly 100% of recipients. It is known that immunity from hepatitis A infection can last for several years after two hepatitis A vaccine doses.

Hepatitis B:

A harmless hepatitis B antigen is given for active vaccination to activate the body’s immune system to develop protective antibodies against the hepatitis B surface antigen. Vaccines currently available in the U.S. are synthesized using recombinant DNA technology. These recombinant hepatitis B vaccines, the Energix-B and Recombivax-HB (hepatitis B) vaccines, are engineered to contain only a part of the surface antigen that is very potent in stimulating antibody production by the immune system. There is no viral component other than the vaccine’s surface antigen and can, therefore, not cause infections with HBV. Hepatitis B vaccines should be administered in three doses, 1 to 2 months after the first dose of the second dose, and 4 to 6 months after the third dose. Vaccinations are given in the deltoid muscles (shoulder) and not in the buttocks for the best performance.

Both pregnant women should have a blood test for surface antigen antibodies to the hepatitis B virus. In addition to the hepatitis B vaccine at birth, women who test positive for the HBV risk transmit the virus during delivery. Thus, infants born to mothers with hepatitis B infection should receive HBIG. The rationale for offering both immunoglobulin and vaccine is that although the hepatitis B vaccine can provide long-lasting, active immunity, it takes weeks or months for immunity to develop. The short-lived, passive antibodies from the HBIG safeguard the baby before active immunity develops.

Hepatitis C and D:

Currently, there is no hepatitis C vaccine. Due to the six different forms of hepatitis C, such a vaccine’s production is challenging. There is no hepatitis D vaccine available. However, since the hepatitis D virus requires live HBV to replicate in the body, the HBV vaccine will prevent a person not infected with HBV from contracting hepatitis D.