BY: K. Sai Manogna (MSIWM014)

- Layer-like microorganism aggregations and the extracellular polymers bound to a solid surface are biofilms.

- Biofilms, innate cells, are ubiquitous and are becoming more and more important in processes that are designed for pollution control including philtres that drip, rotating biological contactors and anaerobic philtres.

- Biofilm processes are simple, efficient, and sustainable because natural immobilization allows excellent retention and accumulation of the biomass without the need for separate solids.

- We should consider a fundamental problem concerning biofilms (indeed all aggregated systems) before designing mathematical instruments for predicting the removal of substrates by biofilm:

Here are a few possibilities:

1. Due to the advection of substrates after the film, these biofilms are exposed continuously to the fresh substrate in space. It means that if the biofilm is attached near the source of the substratum supply, the substrate concentration is higher.

2. In mandatory substratum transportation consortia or other synergistic relationships, different types of bacteria must be co-existent; for the exchange, the near juxtaposition between cells is required in a biofilm.

3. The biofilms build a more friendly internal atmosphere (for example, pH, O2, or products) than the bulk liquid. In other words, the biofilm creates special and self-created cell-beneficial micro-environments.

4. The surface itself produces a single micro-environment, for example by removing contaminants or by corrosive releases of Fe2+, a donor of electrons.

5. The surface allows the bacteria to change physiologically.

6. The cell’s strict packing modifies the physiology of the cells.

Biofilm formation:

The development of biofilms can be divided into five phases:

1. Surface relation

2. Monolayer formation

3. Training in microcolony

4. Biofilm mature

5. Unlocking

- The initial step, which is still reversible, is the initial touch of the moving planktonic bacteria on the surface.

- The bacteria then begin to form a monolayer and create a protective “slime,” an extracellular matrix.

- The matrix contains extracellular polysaccharides, structural proteins, cell scrap, and nucleic acids known as EPS.

- Extracellular DNA (eDNA) predominates the initial steps of matrix development, and polysaccharides and structural proteins later take over.

- At these points, microcolonies are produced that display significant growth and contact between cells such as quorum sensing.

- During the last step of a new cycle of biofilm formation, some cells in mature biofilm begin to detach itself into the environment as planktonic cells.

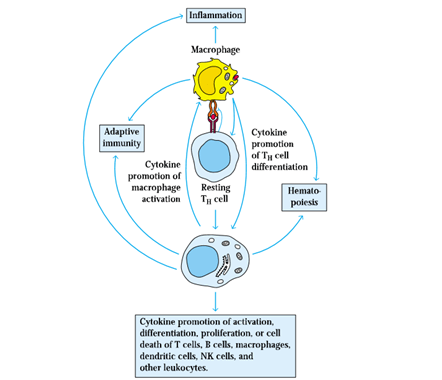

The biofilm allows for:

a. tolerates antibiotic attacks;

b. Trap bacterial growth nutrients and stay in a favourable niche;

c. Adhere and avoid flushing to environmental surfaces;

d. live in close collaboration and associate with other biofilm bacteria;

e. Stop phagocytosis and attack the complementary routes of the body.

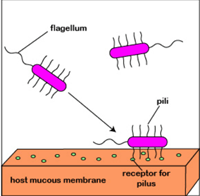

For example, Planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses polar flagella to travel by water or mucus and to reach a firm surface as mucous membranes of the body. The cell wall and pil adhesives can then be used to bind the mucous membrane epithelial cells. Attachment stimulates signalling and quorum sensing genes so that a polysaccharide alginate biofilm synthesization will eventually begin with the population of P. aeruginosa. As the biofilm forms, the bacteria lose flagellum and secrete different enzymes that allow the population to obtain nutrients from the host cells. Finally, the biofilm pillows and establishes water canals for all bacteria in the biofilm to provide water and nutrients. As the biofilm gets too crowded with bacteria, the sensing of quorum helps a few Pseudomonas to develop flagella again, escape the biofilm, and colonize a new spot.

Fig: Formation of biofilm by P. aeruginosa.

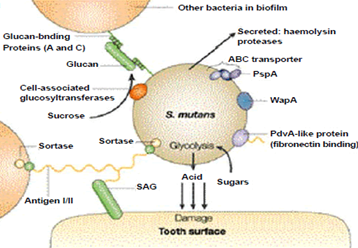

Two bacteria involved in dental caries, Streptococcus mutants and Streptococcus sobrinus, break down sucrose to glucose and fructose. Streptococcus mutans may use a dextransucrase enzyme in a sticky dextran polysaccharide, which forms a biopathic film that allows bacteria to bind to the tooth enamel and form the plaque. The pathogenicity of S bacteria. S. and mutans. In order to generate energy, sobrinus often ferments glucose. Glucose fermentations produce lactic acid, which is released on the tooth surface and causes decay. The mechanism is described in the given image.

Microbial Leaching:

- Copper extraction from ore deposits was carried out over centuries using acidic solutions, but the involvement of bacteria was not confirmed in metal dissolution before the 1940s.

- Today about 10–20% of copper mined in the United States is extracted by low-grade microbial processing. In the expansion of microbial leaching, other elements, including Uranium, Silver, Gold, Cobalt and Molybdenum, are also invested considerably.

- Most microbial liquidation relies on metal sulphides’ microbial oxidation. Aqueous environments combined with mineral waste create very harsh conditions with a low pH, high metal concentrations and high temperatures that select very specialized nutrient requirements for a microbial flora.

- Heap leaching is the most common method in which copper and other minerals are extracted microbially from spent ore.

- The method involves arranging the spent ore fragments into a configuration of the packed bed to allow the passage of water. Acidized water (pH = 1.5-3.0) is sprayed on the porous ore bed in order to start the operation.

- The solvent ferrous iron is actively oxidized, and sulphide minerals are attacked by acidophilic bacteria such as Thiobacillus iron, which can then be released from aquatic ions by releasing soluble cupric ions. In terms of the corrosion on metal surfaces, this oxidation is identical.

Biological reactions and mass transfer rates currently constrain the industrial applications of microbial fluid, but in recent years significant changes have been made to process design, and the mining industry sees the method as being promising.

Removal of Biofilms:

- Traditional cleaning of biofilm has been accomplished by detergents, biocides, enzymes, and mechanical or physical methods of cleaning the biofilm.

- Biofilms in sensitive locations in the food and drink manufacturing industries have grown, leading to problems such as food spoilage, production quality and other nutrient supplementation and insufficient cleaning and disinfection.

- Depending on the medium temperature and relative humidity of these microorganisms, they will live longer after application. The pulp- and paper-based agent for biofilm removal is classified into three groups: chlorine, chlorine dioxide, hydrogen peroxide (hydrogen peroxide), Ozone, antioxidants, and enzymes.

- The cells adhering to the staphylococcus aureus are effectively used in sodium dichloro isocyanurate, hypochlorite, iodophore, hydrogen peroxide and peracetic acid. The most powerful method of extracting adhered large amounts of L was to eliminate peracetic acid.

- Monocytogenes cells remaining on chips of stainless steel after sanitization. Scanning electron microscopy has shown that on chlorine and anionic acid-treated surfaces biofilm cells and extracellular matrices remain better than iodine and ammonium-quaternary detergent sanitizers from which a viable cell is not released.

- Oxidative and antioxidant biocides have long been used, although enzyme use is being studied at present.

- In order to develop a quality management programme in different industries, tanks, pipes, pasteurizers, coolers, membrane filtration units and fillers must be tested, because they help to avoid microbiological hazards and severe financial losses.