BY: K. Sai Manogna (MSIWM014)

For life, water is essential. There must be sufficient, stable, and usable supplies available to everyone. Improving access to clean drinking water will lead to substantial health benefits. Most individuals fail to gain access to clean water. The supply of clean and filtered water to each house may be the standard in Europe and North America, but access to clean water and sanitation is not the rule in developing countries, and water-borne infections are common. There is no access to better sanitation for two and a half billion people, and more than 1.5 million children die from diarrheal diseases each year. According to the WHO, the mortality of water-related illnesses exceeds 5 million individuals per year; more than 50 percent of these are microbial intestinal diseases, with cholera standing out first and foremost.

A prominent public health concern in developing countries is acute microbial diarrheal diseases. Those with the lowest financial resources and the worst hygiene services are those affected by diarrheal diseases. Children under five, especially in Asian and African countries, are the most affected by water-borne microbial diseases. Often affecting developing countries are microbial water-borne diseases—the most severe water-borne bacterial illnesses.

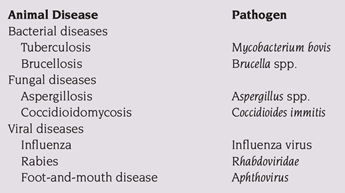

Table 1: Some bacterial diseases transmitted through drinking water.

| Disease | Bacterial agent |

| Cholera | Vibrio cholerae, serovarieties O1 and O139 |

| Typhoid fever and other serious salmonellosis | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium |

| Bacillary dysentery or shigellosis | Shigella dysenteriae Shigella flexneri Shigella boydii Shigella sonnei |

| Gastroenteritis – vibrio | Mainly Vibrio parahaemolyticus |

Indicator Organisms:

1. Microorganisms such as viruses and bacteria in water bodies, which are used as a proxy to determine the existence of pathogens in that area, are indicator organisms.

2. It is preferred that these microorganisms are non-pathogenic, have no or limited water growth, and are consistently detectable at low concentrations.

3. In larger populations than the related pathogen, the indicator species should be present and preferably have comparable survival rates instead of the pathogen.

4. In the monitoring of water quality, different indicator species can be used, and the efficacy of predicting pathogens depends on their detection limit, their tolerance to environmental stresses and other pollutants.

Cholera:

Tiny, curved-shaped Gram-negative rods with a single polar flagellum are Vibrio. Vibrios are optional anaerobes capable of metabolism that are both fermentative and respiratory. For all animals, sodium promotes the development and is an absolute prerequisite for most.

1. The majority of plants are oxidase-positive, and nitrate is reduced to nitrite.

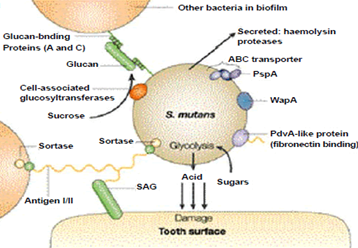

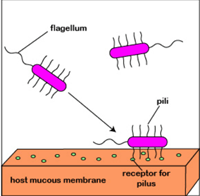

2. Pili cells of some microbes, such as V. cholerae, V. parahaemolyticus, and V. vulnificus, have structures consisting of TcpA protein.

3. The production of TcpA is co-regulated with cholera toxins expression and is a primary determinant of in vivo colonization.

4. Several species of Vibrio can infect humans. The most significant of these species is, by far, V. cholerae.

5. Several forms of soft tissue infections have been isolated from V. alginolyticus.

6. The cells of Vibrio cholerae will expand at 40°C at pH 9-10.

7. The presence of sodium chloride stimulates growth. Vibrio cholerae is a bacterial genus that is very diverse.

8. It is split into 200 serovarieties, distinguished by the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure (O antigens). Only O1 and O139 serovarieties are involved in true cholera.

9. Gastroenteritis may be caused by many other serovarieties, but not cholera.

10. Biochemical and virological features are the basis for the differentiation between Classical and El Tor biotypes.

Disease characterization:

1. The incubation period for cholera is 1-3 days.

2. Acute and severe diarrhea, which can reach one liter per hour, characterises the disease.

3. Patients with cholera feel thirsty, have muscle pain and general fatigue, and display anuria symptoms accompanied by oliguria, hypovolemia, and hemoconcentration.

4. In the blood, potassium decreases to deficient levels. With cyanosis, there is circulatory collapse and dehydration.

Several factors depend on the seriousness of the illness:

(a) personal immunity: both previous infections and vaccines can confer this immunity;

(b) inoculum: disease arises only after the absorption of a minimum quantity of cells, approx. 108.

(c) Gastric barrier: V. cholera cells like simple media and the stomach is also an adverse medium for bacterial survival, usually very acidic. Patients that take anti-acid drugs are more vulnerable than healthy patients to infection.

(d) Blood group: persons with O-group blood are more vulnerable than others for still unexplained causes.

5. In the absence of treatment, the cholera-patient mortality rate is approx—fifty percent.

6. The lost water and the lost salts, mostly potassium, must be replaced.

7. Water and salts can be administered orally during light dehydration, but rapid and intravenous administration is mandatory under extreme conditions.

8. Presently, doxycycline is the most effective antibiotic. In some instances, if no antibiotic is available for treatment, the administration of salt and sugar water will save the patient and help with recovery.

9. Two significant determinants of infection exist:

(a) the adhesion of bacterial cells to the mucous membrane of the intestine. It depends on the presence on the cell surface of pili and adhesins;

(b) development of a toxin from cholera.

Salmonellosis:

1. Gram-negative motile straight rods include the genus Salmonella, a member of the family Enterobacteriaceae.

2. Cells are oxidase-negative and positive for catalase, contain D-glucose gas, and use citrate as a sole source of carbon. There are many endotoxins in Salmonellae: O, H, and Vi antigens.

3. S. Subsp enterica. enterica serovar Enteritidis is the most widely isolated serovariety worldwide from humans. Other serovarieties can, however, be prevalent locally.

4. A fermented juice historically extracted from the palm-tree was the source of insulation.

Disease Characterization:

1. Two forms of salmonellosis can be pathogenic to humans:

(a) typhoid and paratyphoid fever (not to be confused with rickettsia-induced typhus disease);

(b) Gastroenteritis.

2. Low infection doses are sufficient to cause clinical symptoms (less than 1,000 cells).

3. There are different clinical signs of salmonellosis in newborns and children, from a severe typhoid-like disease with septicemia of a range to a mild or asymptomatic infection.

4. The infection is commonly spread through the hands of staff in pediatric wards.

5. Ubiquitous Salmonella serovars, such as Typhimurium, are often caused by food-borne Salmonella gastroenteritis.

6. Symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting, and fever occur about 12 hours after consuming infected food and lasts 2 to 5 days.

7. Spontaneous healing typically happens. All kinds of food can be associated with Salmonella.

8. The prevention of food-borne Salmonella infection is focused on the prevention of contamination, the prevention of food-borne Salmonella multiplication (persistent storage of food at 4oC), and where possible, the use of pasteurization (milk) or sterilization (other foods).

9. When infected with fertilizers of the fecal origin or washed with polluted water, vegetables and fruits can carry Salmonella.

10. The incidence of typhoid fever decreases as a country’s development level grows, such as pasteurization of milk, dairy products, and controlled water sewage systems.

11. The risk of fecal contamination of water and food remains high where these hygienic conditions are absent, and so is the occurrence of typhoid fever.

Bacillary Dysentery or Shigellosis:

Shigella are members of the Enterobacteriaceae family that are Gram-negative, non-spore-forming, non-motile, straight-rod-like. Without gas production, cells ferment sugars. There is no fermentation of salicin, adonitol, and myo-inositol. Cells do not use citrate, malonate, and acetate as the primary source of carbon and do not create H2S. It is not decarboxylated with lysine. Cells are oxidase-negative and positive for catalase. Members of the genus Shigella have a complex antigenic sequence, and their somatic O antigens are the basis of taxonomy.

Disease Characterization:

1. The incubation time for shigellosis is 1-4 days.

2. Typically, the illness starts with fever, anorexia, tiredness, and malaise. Patients exhibit irregular, low-volume, sometimes grossly purulent, bloody stools, and abdominal cramps.

3. Diarrhea progresses to dysentery after 12 to 36 hours, with blood, mucus, and pus appearing in feces that decrease in volume (no more than 30 mL of fluid per kg per day).

4. Even though the molecular basis of shigellosis is involved, the colonic mucosa’s penetration is the initial phase in pathogenesis.

5. Degeneration of the epithelium and acute inflammatory colitis in the lamina propria define Shigella infection’s resulting concentration.

6. Desquamation and ulceration of the mucosa eventually contribute to leakage into the intestinal lumen of blood, infectious elements, and mucus.

7. The colon’s water absorption is hindered under some circumstances, and the amount of stool depends on the flow of ileocecal blood.

8. As a consequence, normal, scanty, dysenteric stools can move through the patient.

9. The bacterium must first adhere to its target cell in order for Shigella to penetrate an epithelial cell.

10. The bacterium is usually internalized into an endosome, which is then lysed to obtain entry to the cytoplasm where replication occurs.