BY : K. Sai Manogna (MSIWM014)

Inflammation is a systemic reaction for several causes, such as tissue damage and infections. An acute inflammatory response typically has a fast onset and lasts for a short time. In general, acute inflammation is followed by a systemic reaction known as an acute-phase response, marked by a rapid shift in the concentrations of many plasma proteins. Persistent immune activation in certain diseases can lead to chronic inflammation, which often has pathological implications.

An essential role of neutrophils in inflammation:

1. The predominant cell type infiltrating the tissue is the neutrophil at the early stages of an inflammatory response.

2. Within the first six hours of an inflammatory response, neutrophil penetration into the tissue peaks, with development of neutrophils in the bone marrow growing to meet this need.

3. An average adult produces more than 1010 neutrophils per day, but during a time of acute inflammation, neutrophil production can increase by as much as tenfold.

4. The bone marrow is left by the neutrophils and circulates inside the blood.

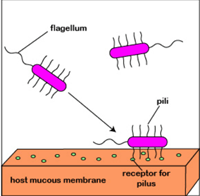

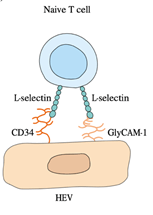

5. Vascular endothelial cells increase their expression of E- and P-selectin in response to the mediators of acute inflammation.

6. Increased P-selectin expression is caused by thrombin and histamine; cytokines like IL-1 or TNF-induce increased E-selectin expression. The circulating neutrophils express mucins such as PSGL-1 or the tetrasaccharides Lewisa sialyl and Lewisx sialyl bind to E- and P-selectin.

7. This binding mediates the attachment or tethering of neutrophils to the vascular endothelium, enabling the cells to roll in the direction of blood flow.

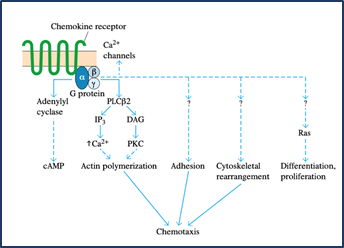

8. Chemokines such as IL-8 or other chemoattractants function on the neutrophils during this time, causing an activating signal mediated by G-protein that leads to a conformational shift in the molecules of integrin adhesion, resulting in neutrophil adhesion and subsequent transendothelial migration.

9. When in tissues, activated neutrophils also express elevated levels of chemoattractant receptors and thus show chemotaxis, migrating up the chemoattractant gradient.

10. Several chemokines, complement split products (C3a, C5a, and C5b67), fibrinopeptides, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes are among the inflammatory mediators that are chemotactic to neutrophils.

11. Furthermore, microorganism-released compounds, such as formyl methionyl peptides, are also chemotactic to neutrophils.

12. Increased levels of Fc antibody receptors and complement receptors are expressed by activated neutrophils, allowing these cells to bind more efficiently to antibody- or complement-coated pathogens, thereby increasing phagocytosis.

13. The triggering signal also activates the metabolic pathways into a respiratory burst, creating intermediates of reactive oxygen and intermediates of reactive nitrogen.

14. In the killing of different pathogens, the release of some of these reactive intermediates and the release of mediators from neutrophil primary and secondary granules (proteases, phospholipases, elastases and collagenases) play a significant role.

15. The tissue damage that can result from an inflammatory reaction also leads to these substances. The aggregation, along with accumulated fluid and different proteins, of dead cells and microorganisms, makes up what is known as pus.

Inflammatory Responses:

A complex cascade of non-specific events, known as an inflammatory response, is caused by infection or tissue injury, which provides early protection by minimising tissue damage to the site of the infection or tissue injury. Both localised and systemic responses are involved in the acute inflammatory response.

LOCALISED INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE:

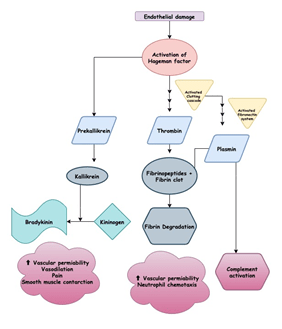

Redness, swelling, pain, heat, and loss of function are the hallmarks of a localised acute inflammatory response first identified almost 2000 years ago. There is an increase in vasodilation within minutes of tissue injury, resulting in an increase in the area’s blood volume and a decrease in blood flow. The increased volume of blood heats the tissue and causes it to turn red. Vascular permeability also increases, leading to fluid leakage, especially in postcapillary venules, from the blood vessels. This results in the fluid deposition in the tissue and, in some cases, leukocyte extravasation, which leads to the area’s swelling and redness. The kinin, clotting, and fibrinolytic processes are triggered when fluid exudes from the bloodstream. The direct effects of plasma enzyme mediators like bradykinin and fibrinopeptides, which induce vasodilation and increased vascular permeability, are responsible for many of the vascular changes that occur early in the local response. Some of these vascular changes are due to the indirect effects of histamine-released complement anaphylatoxins (C3a, C4a, and C5a) that induce local mast-cell degranulation.

1. Histamine is a potent inflammatory mediator, inducing vasodilation and contraction of smooth muscle.

2. Prostaglandins may also contribute to the acute inflammatory response associated with vasodilation and increased vascular permeability.

3. Neutrophils bind to the endothelial cells within a few hours of the initiation of these vascular changes and move from the blood into the tissue areas.

4. These phagocytose neutrophils invade pathogens and release mediators that lead to the inflammatory reaction.

5. The macrophage inflammatory proteins (MIP-1 and MIP-1), chemokines which attract macrophages to the inflammation site, are among the mediators. Around 5-6 hours after an inflammatory response starts, macrophages arrive.

6. These macrophages are activated cells that show increased phagocytosis and increased release of mediators and cytokines that contribute to the inflammatory response.

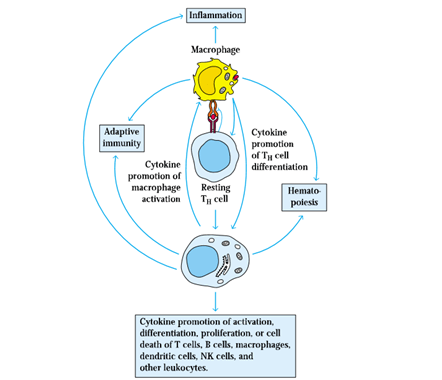

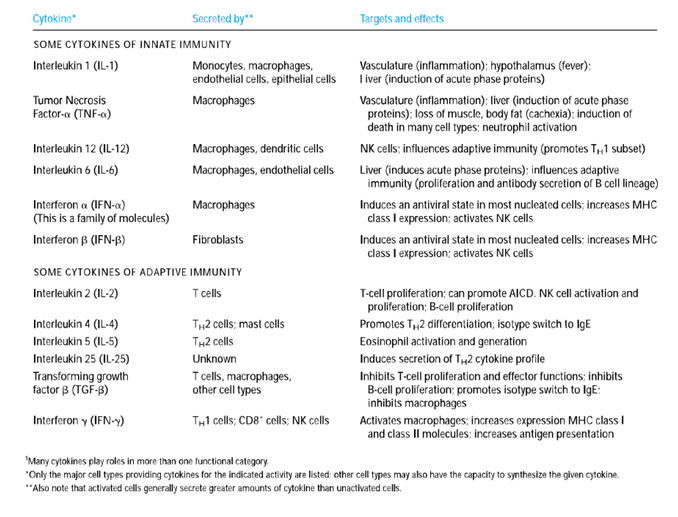

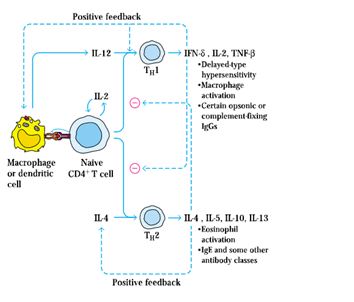

7. Three cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-𝛼) that induce activated tissue macrophages secrete many of the localised and systemic changes, which observed in the acute inflammatory response.

8. All three cytokines function locally, causing coagulation and vascular permeability to increase.

9. Both TNF-𝛼 and IL-1 induce increased expression of adhesion molecules on vascular endothelial cells. For example, TNF-𝛼 stimulates the expression of E-selectin, a molecule of endothelial adhesion that binds adhesion molecules to neutrophils selectively. IL-1 induces increased ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression, which binds to lymphocyte and monocyte integrins.

10. Neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes circulating identify these adhesion molecules on the walls of the blood vessels, bind to them and then pass into the tissue spaces via the vessel wall.

11. IL-1 and TNF-𝛼 also act on macrophages and endothelial cells to induce the development of chemokines that, by increasing their adhesion to vascular endothelial cells and by acting as potent chemotactic factors, contribute to the influx of neutrophils.

12. Besides, macrophages and neutrophils are activated by IFN-𝞬 and TNF-𝛼, facilitating increased phagocytic activity and increased release of lytic enzymes into tissue areas.

13. Without the overt intervention of the immune system, a local acute inflammatory response may occur.

14. Cytokines released at the inflammation site also promote both the adherence of immune system cells to vascular endothelial cells and their migration into tissue spaces through the vessel wall.

15. This results in an influx of lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells to the tissue damage site, where these cells are involved in antigen clearance and tissue healing.

To monitor tissue damage and promote the tissue repair processes that are important for healing, the length and strength of the local acute inflammatory response must be carefully controlled. TGF-β has been shown to play an essential role in limiting the response to inflammation. It also encourages fibroblast aggregation and proliferation and the deposition of an extracellular matrix necessary for proper tissue repair. Clearly, in the inflammatory response, the leukocyte adhesion processes are of great importance. As exemplified by leukocyte-adhesion deficiency, a failure of proper leukocyte adhesion may result in disease.

SYSTEMIC ACUTE-PHASE RESPONSE:

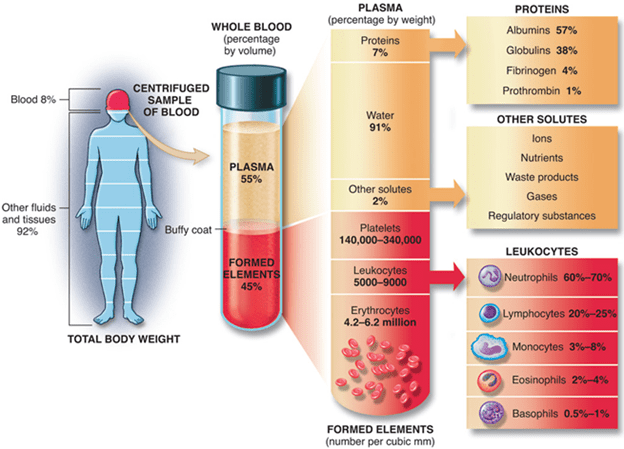

The systemic response is known as the acute-phase response accompanies the local inflammatory response. This response is characterised by fever induction, increased hormone synthesis such as ACTH and hydrocortisone, increased white blood cell development (leukocytosis), and the production of a large number of liver acute-phase proteins.

1. The rise in body temperature prevents a variety of pathogens from rising and tends to strengthen the immune response to the pathogen.

2. A prototype acute-phase protein whose serum level increases 1000-fold during an acute-phase response is a C-reactive protein.

3. It is made up of five similar polypeptides by noncovalent interactions kept together.

4. The C-reactive protein binds and activates complements to a wide range of microorganisms, resulting in the accumulation of opsonin C3b on the surface of microorganisms.

5. The C3b-coated microorganisms can then readily phagocytose phagocytic cells, which express C3b receptors.

6. The combined activity of IL-1, TNF-𝛼 and IL-6 is linked to several systemic acute-phase effects. To cause a fever response, each of these cytokines works on the hypothalamus.

7. Increased levels of IL-1, TNF- and IL-6 (as well as leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and oncostatin M (OSM)) induce hepatocyte development of acute-phase proteins within 12–24 h of the onset of acute-phase inflammatory response.

8. To induce colony-stimulating factors (M-CSF, G-CSF, and GM-CSF) secretion, TNF-𝛼 also acts on vascular endothelial cells and macrophages.

9. These CSFs induce hematopoiesis, causing the number of white blood cells required to combat the infection to increase temporarily.

10. Redundancy in the capacity of at least five cytokines (TNF-𝛼, IL-1, IL-6, LIF, and OSM) to induce liver acute-phase protein development results from the induction of NF-IL6, a common transcription factor, after the receptor interacts with each of these cytokines.

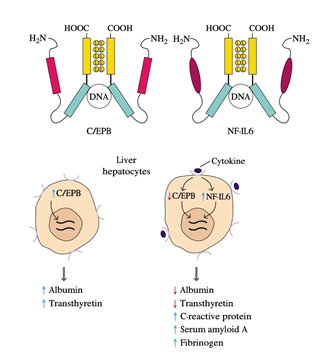

11. Amino-acid sequencing of cloned NF-IL6 showed that it has a high degree of sequence identity with C / EBP, a liver-specific transcription factor.

12. NF-IL6 and C / EBP both contain a leucine-zipper domain and a simple DNA-binding domain, and in the promoter or enhancer of the genes encoding different liver proteins, both proteins bind to the same nucleotide sequence.

13. C / EBP, which stimulates albumin and transthyretin production, is hepatocyte-constitutively expressed.

14. Expression of NF-IL6 increases and that of C / EBP decreases as an inflammatory response arises, and the cytokines interact with their respective receptors on liver hepatocytes.

15. The inverse relationship between these two transcription factors reflects the observation that serum protein levels such as albumin and transthyretin decrease during an inflammatory response while those of acute-phase proteins increase.